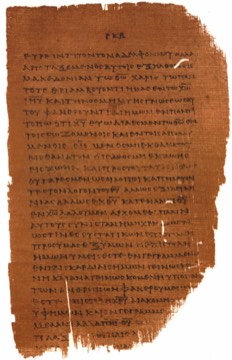

Fulfilling the Scripture

By: Dr. Gregory S. Neal

The Scriptures are precious. I find it amazing that some Christians – usually fundamentalists and conservative evangelicals, including some Methodists – accuse me, and other Progressive Christians, of not having respect for, of not revering, of not loving the Scriptures. Nothing could be further from the truth. I have a deep, abiding respect for the Scriptures. The difference may be in that, while we revere, respect, and view Scripture as the gift of God and a means of grace, conservatives tend to elevate them far beyond their station while presuming that their interpretation(s) of Scripture are the final authority for Christian faith and practice.

Back during the early days of the COVID-19 Pandemic I was on an early morning Zoom call with a bunch of clergy friends. I was still groggy and the coffee hadn’t yet kicked in, and so when one of my friends asked me what I believed about the Bible, I was surprised to hear myself saying:

"The Bible contains an interpretation of God’s presence in the lives of Hebrews and Christians across several centuries, as experienced within multiple cultural contexts, written in the dynamic words of humans, and applied through a careful reflection upon spiritual experience, the formation of religious tradition, and the articulation of faithful reason."

I was so startled by what came out of my own mouth that, with my friends' help, I quickly wrote it down; yes, that’s what I believe about Scripture. There’s a short-hand version of this that I have long used:

We see that conception of Scripture in Jesus’ own use of the Hebrew Bible. We see it in Luke chapter 4, where Jesus is depicted as reading in the Synagogue from the scroll of the Prophet Isaiah, chapter 61. Jesus is depicted as reading the passage selectively; he doesn’t complete the passage, but stops about half-way through the final sentence. He reads and applies this Scripture very carefully - very specifically - making it clear that he’s talking about himself:“The Bible isn’t THE Word of God; rather, the Bible contains the Word of God (Jesus) written in the words of humans.”

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” (Luke 4:18-21)

Many Christians will say that the Bible has been, or is being, “fulfilled.” They’ll often point to specific things happening in the world today to substantiate their claim that the end-times are approaching and that Christ is about to return. And, in doing that, they’re missing the whole point of true scriptural fulfillment. How did Jesus understand himself to be a fulfillment of Scripture, and what did he mean when said: “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing"?

The Word “to fulfill” means to fill up, to complete, to bring to fruition, to conclude, to make real and present and established. Jesus is telling them that this passage from Isaiah 61 was completed and made real through their hearing of it. That’s an amazing thing for Jesus … for anyone … to say. Specifically, what is he saying?

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” (Luke 4:18-19)

That’s huge. “Bringing Good News to the poor” Ok … we certainly get that from what Jesus preaches throughout his entire ministry. For example, in his famous Sermon on the Mount, he said: “Blessed are the poor … for theirs in the Kingdom of Heaven.” Got it!

“Proclaim release to the captives.” Alright … Jesus sets us free from captivity. And, like any good rabbi in Jesus' time, today's preachers are great at interpreting this to mean the captivity of our sins, the captivity of our depression and anxiety, the captivity that our illnesses can cause us. Yeah … it's not hard to spin this as being demonstrated through the forgiving and healing ministry of Jesus. And, in doing that, we’re not wrong. But the passage isn’t just metaphorical, it’s also literal: it speaks about those who are “oppressed” by unjust religious, societal, or governmental systems. In Jesus’ day they would have understood it as the messianic mission of overthrowing the occupation forces of the Roman Empire. Let that sink in for a moment.

We can spin this to make it easier for us to comprehend; we do that all the time, and since Judea remained under Roman occupation for generations after the time of Jesus we should understand this in ways that are more than just literal. But to make this claim complete, to truly bring it to fruition, there is more than just a spiritual component that has to be completed: there’s the reality of it, in the nitty-gritty stuff of this life. Jesus sets us free. Period.

There’s a wonderful old Gospel hymn that has a chorus that proclaims:

“He set me free …

he set me free …

he broke the bonds of prison for me.

I’m glory bound, my Jesus to see,

For glory to God, he set me free.”

Yes … spiritually. Yes … emotionally. But also, for those to be true, there must also be a literal breaking of our bonds. Freedom from actual, physical, temporal oppression. Proclaiming Good News to the poor implies that you’re going to help them; setting free the captives implies that they’re not going to be imprisoned anymore … by anything.

“And recovery of sight to the blind” Yeah … blinded by sin, blinded by cultural norms and standards that cause us to not see reality, not see the evil and oppression around us, not see our own participation in it. But also, Jesus is speaking about real vision ... about people being able to see, again, with their physical eyes. The scriptures contain stories of Jesus healing blind people, enabling them to physically see again, and while explaining the implications of such miracles Jesus explains that it's possible for us to physically see while, spiritually, still being blind. In other words, there’s more to vision than seeing with one's eyes: there’s comprehension and understanding, there’s being freed from the blindness of our own oppression, and there's being freed from the oppressive blindness others.

There’s a branch of Christian thought called Liberation Theology in which one of the functions of the Messiah is liberation from oppression. This theological approach views the entire work of Christ as being directed toward our deliverance from oppression: sin, sickness, cultural injustice, personal and social holiness … all of these are viewed from the perspective of liberation. Jesus fulfills these scriptures by liberating us from the shackles of spiritual, emotional, and physical slavery. I've always liked that approach.

“…to let the oppressed go free.” From this it should be no surprise that Liberation Theology has a huge cultural and political component, and it takes its scriptural mandate from Christ’s calling. There are many ways that we are among the oppressed, and there are many ways that we are also among the oppressors. Being delivered from oppression often means being rescued from the oppression of our own oppressiveness — from our own participation in the sins of social and cultural injustice, white supremacy, privilege and racism, economic injustice and the cycles of poverty, ecological indifference and the abuse of God’s good creation, heteronormativity and culturally conditioned gender roles. Our society’s participation – and our own participation – in any and all of these oppressive realities is why Christ has come to deliver us.

“Oh, Greg, certainly Jesus wasn’t talking about politics and economics! He was speaking only spiritually, right? He was talking about emotional and spiritual oppression. Right?”

Well ... let's see: “…to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” Yes, Jesus delivers us from emotional and spiritual oppression. However, we would be remiss if we ignored the fact that emotional and spiritual oppression is part of the deeper dynamic of the oppressive systems in which we find ourselves. Jesus also calls us to deal with the physical, political, and cultural oppression which so horribly exacerbates our emotional and spiritual sickness. We see this in that last term: “The Year of the Lord’s Favor.”

That’s a direct reference to the concept of a “Year of Jubilee” found in Leviticus 25. Every fifty years in Hebraic society there was supposed to be a massive cultural reset: all debts were to be cancelled, all stolen or unjustly acquired property was to be returned to its original owners, and everybody was to be kind and generous with everybody else. The Year of Jubilee never actually happened, but it was an ideal that was deeply rooted in the Hebraic conception of justice and righteousness. Jesus proclaimed himself, his ministry, and his calling to be one of bringing the Year of Jubilee into to fruition. And Christians view, in Jesus, all of this as being fulfilled: spiritually and, indeed, physically. When we talk about Jesus forgiving the sins of the whole world, that affirmation is rooted in this idea of Jubilee. However, it’s more than just the forgiveness of sins; it’s more than just wiping out our trespasses and our many spiritual debts; it’s also about resetting the entire cultural and social matrix by wiping out all forms of injustice.

That was Jesus’ calling to ministry. As Christians, this is also our calling to ministry. And, by doing these things, we join Jesus in fulfilling scripture.

“That’ a tall order, Greg!” Yes, it is.

“We can’t do those things … that’s above our pay grade!" Really? I don’t think so. The Church is called to be about changing lives: both spiritually and physically. We’re called to preach the Good News to the poor, to proclaim release to the captives, to enable the recovering of sight to the blind, to set free the oppressed, and to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor. That’s how we fulfill Scripture ... not by trying to build a denomination that will be free of sinners that we don't like.

I’m sorry for getting a little too church-political, here, but I can’t avoid it. Some Methodists are wanting to rid themselves of those whom they perceive to be sinners, either by getting rid of those with whom they disagree or by leaving, themselves, to form a new denomination that would exclude those sinners. However, the Family of God doesn’t work that way. Oh, they can leave, and many will, but the oppressed are going free, the poor are being given Good News, those blinded by social and spiritual oppression are being given new sight, and the Year of the Lord’s favor is to be proclaimed. That was Jesus’ calling to ministry; and, that is our calling.

© 2022 Dr. Gregory S. Neal

All Rights Reserved

As a popular teacher, preacher, and retreat leader, Dr. Neal is known for his ability to translate complex theological concepts into common, everyday terms. His preaching and teaching ministry is in demand around the world, and he is available for public engagements. He is the author of several books, including Grace Upon Grace: Sacramental Theology and the Christian Life, which is in its second edition, and Seeking the Shepherd's Arms: Reflections from the Pastoral Side of Life, a work of devotional literature. Both of these books are currently available from many book stores, including Cokesbury, Barnes And Noble, and Amazon.